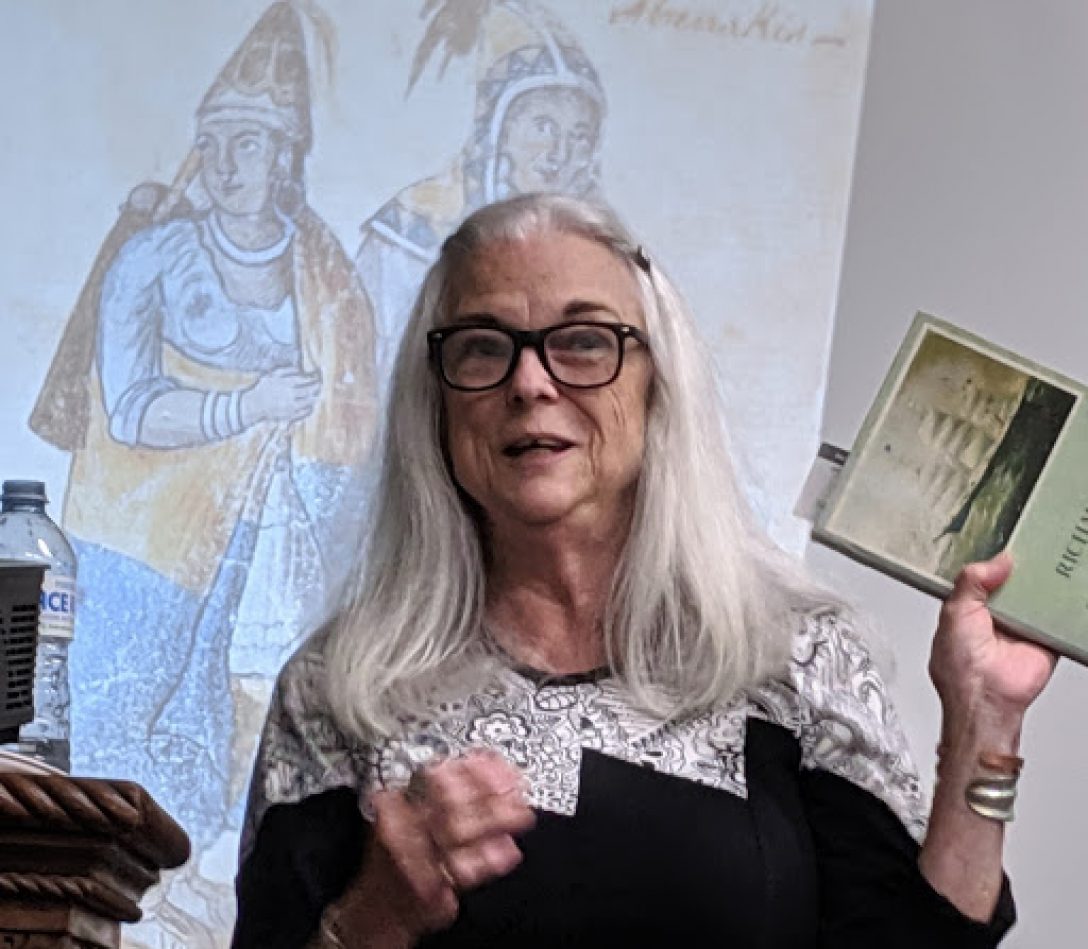

SENATOR ANGUS KING ~ T. BLEN PARKER at book signing:

FIND SWAN ISLAND in the KENNEBEC at:

GULF OF MAINE BOOKSTORE, MAINE STREET, BRUNSWICK, MAINE

SHERMANS BOOKSTORES of MAINE

AMAZON.COM and BARNESANDNOBLE.COM

SWAN ISLAND IN THE KENNEBEC

JOURNEY TO SOWANGEN – ISLAND OF EAGLES

ISBN: 978-1-59713-198-8

AN HISTORICAL NOVEL

by T. Blen Parker now available

FREE READs :

FIRST CHAPTER:

Long before Zanoba was yet born in 1593, scarlet flames from a bonfire reached their curling tongues higher and taller against the blackened sky as tribal elders performed their storytelling dance, throwing long shadows across the ring of engrossed villagers. Representing many gens (families, tribes or bands) of Wabanaki, the People of the Dawnland came from territory between Eastport south to York all along the northeastern seacoast, extending westward toward their sacred mountain Mount Kineo, where legendary Gluskap created all life, as the Abenaki Confederacy understood it. Great sea eagles soared through the skies, not to be taken for granted, however. One never knew whether a spirit-guide might be watching native activities.

Passing a large lobster-claw pipe, sun-bleached red and filled with dried nicotiana rustica leaves to the brother at his left, Zanoba’s grandfather, Awasos, (born in 1564 to a 16-year-old native maiden), sat nearly motionless in the circle at the fireside watching the lively dance long into the night. Later, when the moon rose higher in the sky, the dance gradually wound down, and quiet prevailed blanketed by the silvery moonlight. Native children slumbered near their mothers on luxurious fur-covered spruce-bough beds. After chasing each other all day even the village dogs were silently lounging at the perimeter of the bark huts, ears perking up at the slightest alert of danger from deep within the forest. The only sounds were occasional echoes from a pair of gokokhoko’s emitting a repetitive hoot-e-hoot, hoot-e-hoot call throughout tall trees in the distance. Except to flick off stray sparks landing like darts on darkened, weatherworn bare flesh, all present appeared hypnotized by nesting rings of smoke rising higher and higher from the communal claw pipe.

Verbal confirmations and forthcoming answers to their questions were expected at the conclusion of the dancing when the fire quieted down. All present then moved in closer to his brother, tightening the circle into a more intimate gathering where finer details of their history could be learned. Each man could feel the body heat, feel the breath, and nearly hear the rapid heartbeat of the brother next to him. The women and girls quietly listened from the outer circle of huts as they tended to sleepy children until they drifted into deep slumber. Females had their own conference, held in quiet whispers, speculating what direction the gen might take, what the impact might be on their, and other connected villages, prepared to vote when the men were done conferencing. They were the proud people of the Wabanaki First Nations who called their land Ketakamingwa, meaning the ‘big land on the seacoast.’ Believing the Great Spirit Gluskap created them, the People of the Dawnland lived between their sacred Mount Kineo and the rocky saltwater coast from Eastport to York, Maine, where the sun first meets Mother Earth each morning. Particularly during that time, Natives treasured spirit-guides, some recognizing bears, coyotes, wolves, turtles, sturgeon, snakes, or perhaps eagles. However, until a native spent time in deep reflection, or faced a life altering circumstance, it was often only creatures recognizing their status as spirit-guides.

Numerous interconnecting rivers, streams, ponds, and lakes provided the only existing inroads to more densely forested areas. Carrying places provided short dry land paths across which canoes must be carried on the shoulders of two or more hardy souls from one body of water to the next, allowing a continuous route of access to their destinations. Abenaki bowmen marked trees with graphic symbols leaving a map for the safest routes used by traveling brothers. Boulders, granite ledges, swampy areas, muddy creeks, downed and rotting trees, or stumpage prevented their fast travel by land. Only well-worn footpaths provided access to inland areas. No roads yet existed, were unknown and unnecessary. Horses, wagons, and carts did not arrive on the scene until years later. Hunting, trapping, or fishing in those areas linked by land paths offered not only food but furs for clothing and bedding in their birch bark and fir bough lodges.

Awasos, Zanoba’s grandfather, a young man of 20, was the first eager voice to make an inquiry of the dancers when they squatted to rest their bottoms on their heels or sat on the furs spread on the ground before them. One of the brightest in the village, Zanoba’s grandfather asked many questions and could offer exacting solutions to daily challenges using his sharp mind, innate curiosity, and ability to listen. Unarmed, Awasos had been fearless the day he saved a young girl from an attacking wolf, receiving a nasty wolf bite through his right hand. Despite the herbal wraps, bark teas, and berry concoctions, the altercation took the smallest finger and left a jagged toothsome scar in the center of his palm additionally visible on the back of his hand. Thankful to have retained his hand at all and to have saved the girl unharmed, he continued feeling rewarded through the respect of his people who elevated his status to that of a living legend. All brothers in attendance on that day were looking for guidance on their next steps for whatever was the most beneficial direction for their gen. Native Americans, including the Abenaki people, thought collectively about any action for the benefit of a group rather than harboring selfish individual pleasures or gains before considering the family.

With the talking-stick in hand, Awasos stood up, as was customary when addressing a question to the elders. He stood straight, a handsome brave of six foot, three inches in height, holding the talking-stick outward from his body. Reaching out his scarred, 4-fingered hand, he lifted the massive crustacean claw to his lips, taking a long draw of tobacco smoke into his lungs. Straightening his spine to full height, he raised his eyes to the sky. Blowing several stacked rings of smoke into the air, he licked his thick parched lips before beginning to speak. Many pairs of flint black eyes were trained upon him as he began to speak. “More strangers have followed in great wooden ships blowing across the sea under big white clouds. Fifty-eight of our family members were taken as captives (and sold into slavery in Spain). Robbed of the vast and abundant namas that swim in our rivers maybe they will trick more brothers or sisters into joining them in floating away this day. What action would you advise to prevent these losses to our family? How much more of our lives can we watch slipping from our hands before all is gone and our ancestors forgotten?” Concluding his question, he passed the talking-stick to the brother next to him, and each passed it swiftly along to the next with many moments of silence until it returned to Awasos, who had waited to hold it again for what seemed to him years of silence.

The elders remained seated on layers of luxurious bear pelts, nodding among themselves for many moments following Awasos’ question, his pearly white upper teeth involuntarily clamped down on his thick bottom lip, nearly biting through as he waited. He had voiced the question everyone seated at the fire had in their minds although few would have found the fortitude to ask. Awasos also knew when the spokesman began that it was his responsibility before receiving any variation of agreed-upon ideas first to present a working version of the solution. It was their way, their tradition, their teachings, he understood.

Time seemed suspended just then until more pegues swarmed to attack. Brother Ahanu arose to tend the dying embers, poking at the fire pit in a daze, prompting spires of brilliant yellow, crimson, pearly blue, orange, and sea green to fly high up into the cool night air. The smoke and heat of the fire would afford some comfort, keeping away the pesky chomping insects! The bear grease and mint leaf they wore as a skin treatment helped only just so much to ward off the annoying pegues. Many pairs of large coal black eyes reflected bright sparks shooting from the campfire and the glow of stars as they waited. Awasos slowly sat down on his fur cushion, mindlessly stroking the thinning sole of his left moose hide moccasin in a slightly circular motion with his thumb as he sunk deeper into his thoughts, regulating his breathing. The lobster claw pipe continued to silently circulate, allowing those who had witnessing the storytelling dance a few moments of freethinking.

Awasos returned to simpler memories during that moment, vividly remembering having watched as his grandfather hollowed a log from a downed tree destined as a canoe. He could not imagine how the log could be transformed into any sort of watercraft. In his minds eye he saw his grandfather first gouge down along the center length of the log, and then slowly burn the insides with charcoal embers until enough charred wood could be scraped out. This process formed the interior of a sturdy and heavier canoe that could sometimes accommodate as many as 19 of their village people.

Awasos had learned the second canoe design and was honored to participate in building a lighter boat construction. This design, his grandfather had explained, was made from layers of birch bark meticulously peeled in large sheets by skilled hands and sewn together with strong cedar roots. Lastly, all seams between sheets were caulked, or waterproofed with pitch from the numerous pine and spruce trees spread across the land. Awasos had not forgotten his wonder at the magic of seeing so many nearly identical sheets pulled from one piece of birch tree. He remembered the bottom of the canoe being lined with lengths of sturdy bark, allowing the weight of passengers to step into and down along the length of the craft.

As a young boy, he had repeatedly walked back and forth on the bottom of the nearly finished canoe while his grandfather was otherwise occupied with finishing details of the canoe. Generations since have copied and used their original Native American design without improvement or change for over three centuries. Other Abenaki inventions Awasos remembered were durable moose hide moccasins and snowshoes, practical designs that continue to be utilized in our current lifetimes in harsh Maine and other New England climates. Ash and birch bark baskets and containers were invaluable in collecting water, gathering berries, groundnuts, roots, and Indian tobacco leaves. Birch bark pots were used in cooking some foods and baskets were used in storing dried corn or seeds. Tools were mainly crude edged but sturdy enough to survive the elements, only a few continue to be found intact to this day. Mount Kineo arrowhead-points and flint seemingly never decay as evidenced by several local archeological digs dating up to the year 2017.

At last, the Elder spokesman reached to grasp the talking-stick from Awasos, which he handed directly back inviting Awasos to speak before them with a consensus of his well-considered solution. Awasos stood again as straight as possible, glad to climb out of his sitting position after so long. A puff of wind blew bonfire smoke in his direction stinging his eyes but did not deter him from speaking his solution. He held the talking-stick firmly in his left hand. Even if his idea was not considered a good one, he knew the group would support him, adding enough suggestions to form at least a mindful alternative.

“I believe when Gluskap set us upon Ketakamingwa he had a plan for all time. He has sent many signs to show us how to survive using all that he and Mother Nature have provided. Maybe he did not know of the men who continue to float from far across the vast lake of salt who come to steal the resources of our ancestors.” As he spoke, Awasos outstretched his arms, making an arc in the air around him as he was talking of the vast ocean. “If Gluscap did foresee these things, he could not have had knowledge of their devious and selfish ways. It is our challenge to become friendly and encourage these men to share our bounty, to work together for the good of the land. We have learned peaceful ways with some of our brothers to the south that were not friendly at first contact. We know these men can be kind. Our brother to the south, Sachem Messamouet, visited their land across the water (France) and returned to report to us that he was treated well in the house of the Mayor of Bayonne years ago. We know it is possible with others! We have furs to offer in trade for what they might bring from their strange land far away, and we may find these items useful in our villages. We have gifts of golden bracelets or shiny swords and coins from visitors to Mawooshen and Norumbega long ago. We know not what more shiny metal objects they might have to trade for our furs.” Awasos concluded by saying, ‘Let us be friendly and fair in sharing but wary of aggressive behavior or tricks to capture any of our people.'” He was astonished when the elder spokesman stayed seated, did not reach for the talking-stick, and nodded in unison with all the others. Awasos’ idea was successful in that part of the territory for close to 100 years.

*******************************************

WIDDEN-NOBLE ABENAKI RAID ON SOWANGEN

FROM: SWAN ISLAND IN THE KENNEBEC by T. BLEN PARKER – PAGE 347 –

Lieutenant James Jones Whidden first married at age 20 in March 1734. His first wife was Abigail Sanborn Whidden (1716–1768).

He later moved his family to the south end of the island where they had a full view of the Kennebec River both upriver and down, enjoying views of Dresden as well as Bowdoinham, part of which is now Richmond. The Plymouth Company granted Lieutenant Whidden 325 acres of land on Sowangen in 1756, for his service at Louisburg. He married his second wife Mary Gould at age 27 in 1740 in Rockingham, New Hampshire. Their first daughter, Martha Gould Whidden died in infancy. Abigail Gould Whidden and Nabby Gould Whidden were born on the island where the family built a large, garrisoned home. Son, David Gould Whidden, was also born on Sowangen.

Lieutenant Whidden became friendly and comfortable trading with the Abenaki who visited the island, across from where Chief Kenebiki had lived in his stone fortress on little Swan Island. During that same year, the newly settled “Dunbar towns” included Walpole (South Bristol), Townsend (Boothbay), New Castle (Newcastle), Witchcassett (Wiscasset), and Harrington in Washington County, Maine. “Pejepscot towns” encompassed Brunswick, Topsham, and Georgetown. Major Samuel Goodwin, the resident Kennebec Proprietor, lived in a garrisoned house where Pownalborough Courthouse is today. The major was directed by the Proprietor’s Agreement to set aside two lots in each town, one for the first ordained minister, the other for a parsonage and the minister. Major Goodwin felt nearly as much responsibility for residents within his jurisdiction along the Kennebec as he did for his family members.

James Jones Whidden went on to have children: Samuel Gould Whidden, Sarah Gould Whidden, Simeon Gould Whidden, and Elizabeth Gould Whidden, probably all born in Truro, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Lazarus Noble married Abigail, daughter of Lieutenant James Jones Whidden of Portsmouth, New Hampshire in 1750, leading those families to establish permanent residency together on Sowangen. The Kennebec River Valley (Quinnebequi) was the main highway into prime fishing, hunting, trapping, and possible farmlands on the fertile intervals bordering the rivers and streams. The territory had been a pantry, from which the Abenaki had sustained themselves, and before them, the Red Paint peoples back into the Paleo time period.

Driven by the king’s charters to claim certain portions of the property, reported by previous explorers to be lushly forested, rivers and seas teeming with huge fish of all kinds, and streams flowing over steep falls, providing waterpower for factories and mills. Englishmen came in waves to claim Abenaki territory. Certain bushes such as the sassafras or angelica and other herbs produced the much sought-after medicinal and culinary elements. Europeans coveted sassafras as a cure for syphilis, then rampant on that continent. Angelica was a popular remedy administered by a midwife for the birth mother’s comfort following the birth.

On the evening of 6 September 1750, Major Samuel Goodwin visited his friend Lieutenant James Whidden and his son-in-law, Lazarus Noble at their large garrisoned, two-story home at the south end of Sowangen. Samuel was in a serious mood, his face flushed, his eyes wide and there were deep creases of concern above his bushy eyebrows. Major Goodwin, a Kennebec Proprietor who lived in a fortified residence a short distance upriver near Hathorn Rock (across the river from Indian Point), had come to issue a warning about impending raids by the Abenaki. Neither James Whidden nor Lazarus Noble was willing to accept the caution. Whidden was confident in his friendly trade relations with Chief Kenebiki as well as Chief Abigadasset on the western bank of the Kennebec River, and Chief Robin Hood of Arrowsic Island, a few southerly miles distant and on the eastern side of the Kennebec toward the sea.

“It is about to happen soon, and I tell you it will be swift and violent.” The major raised his voice to impress upon his friend James, further emphasizing his passion by pounding his fist down on the tabletop so hard it startled Mrs. Mary Gould Whidden, Abby Noble, and some of the older children who remained awake in nearby rooms of the garrisoned house they shared. The major continued to inform them that, “The reason those Indians are so upset is due to the assault at Sheepscott. I rode over to Pemaquid to glean more knowledge of Indian activity and whether those fishermen thought there was agitation in the air. Likewise, I know some of those ‘Praying Indians’ (Abenaki converts of Jesuit priests who lived within their village) in Norridgewock have worked themselves up too. Captain Phips has received word via a messenger sent from Commander Jabez Bradbury of Fort George, expressing his concern that over 65 Indians had marched from Penobscot to invade Sheepscott.”

Lieutenant James Jones Whidden promised quietly to keep the children and women inside the garrison for a couple of days but insisted on working in the fields with his son-in-law, Noble, and his sons and grandsons would need to go on each day as usual. He was steadfast in his beliefs that he had in the local Abenaki, trusted friends. He had been trading with those Abenaki for a couple of years without problems, managed to learn much about his neighbors, and respected their wishes. Why he even felt a sense of security from what he perceived as their “protection.” James Whidden was aware of other settlers who were not as respectful of the Abenaki and discouraged them from any attempt at trading, certainly not to venture farther into the wilderness or upriver much above Sowangen.

The visit between Major Samuel Goodwin and James Whidden lasted long into the night. The major excused himself at dawn, attempting to travel the river while it was quiet, proposing to continue his alerts to Fort Richmond, issuing the same warning to Captain Lithgow. He was left frustrated and worried, paddling energetically upriver toward Fort Richmond and his garrison house beyond on the east side of the river at Pownalborough.

The point Major Goodwin was attempting to make to his friend was that Abenaki had been showing signs of agitation for days. War whoops were heard throughout the forest during the days as bowmen ran along footpaths, and long nights of drum beating echoed up and down the river. To further reinforce his point, Samuel Goodwin looked Lieutenant Whidden straight in the eye to tell him that he had visited Sheepscott from a close distance where he observed some of the actions within the local Abenaki villages along his journey without much reaction from his friend James. Any details of his trip to Sheepscott told by Major Goodwin to Lieutenant Whidden were not comforting or positive information.

The next morning was unusually peaceful on Sowangen, lulling Lieutenant Whidden into complacency even as he considered Major Sam Goodwin’s warning. Stepping outside, he took a deep breath of morning air as he assessed his surrounding property, looking sharp through the fields and woods. He reassessed his gut feelings and as he did so, noticed a stately eagle circling in the sunrise far over the entrance to the Eastern River. Seeing the familiar regal eagle added to his complacency. Everything seemed normal on the little island. The eagle had a nest on Spaulding’s Island, nothing more than an outcropping of trees on a half-acre island at the head of little Swan Island, north of his property on Sowangen.

When he returned to the kitchen, he cautioned the women who were up to tell the young girls to stay inside the compound for a couple of days. Unfortunately, everyone neglected to impress upon his young grandsons the importance of not venturing outside the gate that morning, not fully believing what their grandfather considered Major Goodwin’s outrageous warning. The boys did manage to sneak outside the gate just because they thought they could, but hearing voices back at the house, felt guilty thinking they had gotten away with something forbidden. Quickly they retreated inside the fenced-in yard—somehow without remembering to close the gate securely.

The household servants of the Noble-Whidden family were rushing around the kitchen that morning preparing a harvest and birthday celebration for the family. Just after a couple of hungry young ones came trundling down the stairs from their beds, decorating began as promised the night before as a bedtime incentive, and plates of multi-colored sweet cakes of all sizes had been laid out. The activity created a playful, carefree mood throughout the house. James Whidden was sitting in his favorite chair, giving horsy rides to little Fanny, who was giggling so much James had to hold his stomach. What a delight that child was to James, who enjoyed a houseful of activities among his extended family.

Everyone was in the gayest of moods when suddenly a dozen painted Indians stormed directly into the house making angry whooping noises, jamming sweet cakes into their mouths, ripping down the decorations, and pouring vessels of milk across the kitchen floor. One of the Indians began grabbing crocks of sugar, flour, spices, and molasses, overturning them onto the floor, smashing mugs and various crockery on the hearthstones, laughing all through his uncouth antics, satisfied with his mess. Another decided to stomp the wooden kitchen chairs, breaking them up with his heavy war club while piling the splintered wood in the middle of the parlor with any other flammables he could quickly grasp. Still, another wrestled with Timothy Noble, stronger than he looked.

Much to the horror of one of the servants, an already tearful one-year-old Fanny Noble was scooped up like a sack of corn under the arm of a muscular, tall, young Indian. She was last seen being carried down over the hill to be loaded into one of several hidden canoes down on the riverbank. All during this time, screaming, yelling, and loud smashing frightened everyone present including the invaders who quickly began jumping on the upholstered furniture, slashing the upholstery with ghastly-looking knives, and tossing metal cookware about by earsplitting clanging noises as the pans hit. Every member of the household was horrified and paralyzed to do anything in their defense. A few of the other Natives stopped whooping and began to take members of the Noble-Whidden families and their neighbor’s captives.

The lieutenant’s son-in-law, Lazarus Noble, and a hired man scrambled as silently as possible to nearly fly up the back stairs of the garrisoned house, attempting to fire upon the Indians in the yard with no success. Even before they slipped back down the bottom of the stairway, they could see waves of feathers flying, heard fabric ripping and women screaming. Featherbeds had been slit to reveal the goose down feather stuffing, and the Abenaki were enjoying their “snowstorm,” while sliding barefoot through the molasses, as if they thought they were ice skating on the river, cackling away like hyenas as they slid. Under other circumstances, the fantastic performance would have prompted great peals of laughter from the audience.

At least they did not show violence toward any persons, but the children were all so frightened they were crying and yelling for their mothers as some of them were carried outside and down to the riverside. One of the servants had made his usual morning trek to the barn to collect eggs and managed to escape capture by hiding under the floorboards of the barn. Lieutenant Whidden pulled his wife Mary Gould Whidden by the arm down into the root cellar to hide until the Abenaki tired of destroying the house and furnishings. When everything became quiet above them in the house, they smelled smoke and the couple realized they might be the sole survivors of their combined family.

Lieutenant James Jones Whidden grabbed panicked Mary’s hand, pushing her outside into the woods behind the house. Scarcely any clothing to cover themselves, he led her through the dark underbrush for a frightening barefoot trek along the three-mile island ridge, emerging at the north end where a huge boulder sat in a thick stand of bushes on the riverside, just across from Fort Richmond. There, they began to yell out to the commander of Fort Richmond, Captain Lithgow for help, waving their bare arms out from behind the leafy brush cover.

The captain sent one of his men over to the island to investigate the reason for the panicked cries for help. As the soldier paddled closer to the shore where he could hear them, he asked the couple what was the severity of their situation. They shouted back that their garrison was under attack by Indians and some of their family members had been kidnapped. They smelled smoke and thought the house was in flames. Feeling he too was in grave danger; he veered his canoe away from Sowangen to return to the fort at high speed. He immediately reported to Captain Lithgow, saying that the Indians “had murdered Lieutenant Whidden and his whole family.” Nearly chuckling at the insanity of the comment in an otherwise grim situation, Captain Lithgow assured the soldier that he must be mistaken, as he had personally heard distressing shouts for assistance coming across the river from the riverbank just moments prior.

The soldier continued to insist on his original statement, reinforcing his unreasonable assumption by stating with his shocked, pale face, “It is certain, for I received the news from Lieutenant Whidden’s own mouth.” If the actual event had not been so severe, both men would have been bowled over with laughter! Unfortunately, the report was mostly accurate except for the fact that Lieutenant Whidden himself and his wife were still living. Captain Lithgow shook the soldier by his shoulders, looking him directly in the eye, saying, “Buck up soldier, we have a rescue to conduct.” The soldier recovered from his embarrassment on the return trip bringing clothing for Lieutenant James and Mary Whidden to cover their naked bodies, quickly ferrying them across to the safety of Fort Richmond. During the less than five-minute paddle, he nervously looked this way and that toward both shores so quickly the Whidden’s thought his head would snap off. That evening, approximately one hundred Abenaki surrounded and violently assaulted the fort.

Fortunately, Captain Lithgow had taken Major Goodwin’s warnings seriously, briefed his soldiers, readied cannon, rifles and ensured there was enough ammunition, barricading the massive, thick gate, and was as prepared as he could be to resist with all his might and power. By then, the Whidden’s had obtained suitable clothing to cover themselves but were trembling again although confident the fort would provide the protection they did not have at their unsecured garrison that very morning.

Captain Lithgow owed a huge debt of gratitude to Mr. Jennings, a fervently religious resident of Dresden who chose not to heed Major Goodwin’s warning to stay off the river and prepare for an Indian assault. Mr. Jennings opted to shave shingles, as was his usual habit, claiming his God would protect him from any undue harm. However, several of the Indians captured him on their way to attack Fort Richmond that day. Through torture, Mr. Jennings uttered only one “white lie,” in telling his captors that the previous night Major Goodwin had entered Fort Richmond with “many soldiers” to ready for battle. The Indians satisfied themselves by slaughtering nearly a dozen cattle, which they butchered, packing the bloody chunks of meat into several retreating canoes. Mr. Jennings traveled with the Indians by canoe until being marched into Canada and thrown into a prison where he eventually died of starvation.

Mr. Pomeroy, another resident of Dresden, was in the field tending his cattle that day when he realized Abenaki were pursuing him. He ran toward his house, but a small party of Indians who crossed the river to Frankfort (Dresden) slit his throat as he was standing at his front door. Mr. Davis a gentleman then living in an apartment in the house of Mr. Pomeroy, sprang to his door to find an Indian shoving his gun barrel inside to prevent closure of the door. Davis and two women inside the room wrestled with the firearm to defend themselves. Davis’ child was in the summer kitchen of the house and was quickly taken captive. His son gone, Mr. Davis ended up with only the firearm as a trophy of the scuttle to recount the gory details of the attack and kidnapping of his son with his friends.

On the west shore of the Kennebec above Fort Richmond was a point of land called Indian Point, across from where Pownalborough Courthouse stands today. The raiding Indians took the butchered cattle meat, Mr. Jennings, and the thirteen captives from Sowangen to camp on Indian Point that night to rest, furthering their plans before moving northward to Canada. There was such a body of agitated Indians after the raid that their celebratory noises echoed up and down the river and through the thick woods as far upriver as Nahumkeag Island throughout most of the smoke-filled night on the Kennebec River.

The day following the raid on the Noble-Whidden family in 1750, Lieutenant Whidden could not bear to wait any longer, having recovered from nearly suffering a heart attack with all the panic of the morning previous. The acrid odor of smoke still hung in the air and could still be seen rising from the south end of the island. Mary Whidden was as anxious as her husband James to discover what the level of actual damage was at their garrisoned home on the island and whether any of the family or neighbors had survived as well. They did not know then whether any of the household had been murdered, later realizing none of their family or servants had been killed, at least during the raid on the island. Cautiously in the early morning to see what was left, they paddled across the river in a canoe loaded with borrowed rifles from the fort. They were not calmed to discover that thirteen members of their family had disappeared with the marauders. What happened to them? Were they still breathing, were they being paddled upriver, were they being tortured?

Months, or in some cases years later, some of the ransomed or released captives returned from Canada to report they did not sustain any torture, in fact, were treated humanely and with unexpected gentleness, although food had not been plentiful along their rough journey. The raiding Indians were believed to have been young rogue Indians from the Pemaquid settlement, who had worked themselves into fits of anger, not understanding what they perceived as passive attitudes of the elders, sachems, or even of Chief Bomazeen. The braves believed they were going to change the white men; and teach them whose land they were stealing. The small group thought they would make big money by ransoming the captives in Canada. Lazarus Noble, one of the kidnapped, was released but forced to leave three of his children in Canadian captivity. A census report from 1754 shows Lazarus Noble farming on Sowangen. Lazarus, of Scotch descent, was born in Dover, New Hampshire, and died on Sowangen in 1763. One of his sons married after the raid on Sowangen, choosing to settle in Nova Scotia, Canada, and one daughter willingly stayed with the Indians in Canada.

The brother-in-law of Governor Vaudreuil (M. St. Ange), a wealthy man, had purchased freedom from the Natives for one-year-old “Fanny” Noble. Mrs. St. Ange adopted Fanny in her heart, renamed her Eleanor, taught her a life of privilege, and around her 10th birthday, placed her in a nunnery in Montreal to get a good education. Treated to a genteel and refined education there, “Fanny Noble” became a polite, accomplished, agreeable young lady. At age fourteen, she faced another relocation when Samuel Harnden of Woolwich, sent by Fanny’s father, obtained an order issued by the then-acting (Massachusetts) English Governor Spencer Phips to return her to Sowangen where her father lived. Her sophisticated education prevented her from resisting Mr. Harnden’s efforts to carry out the orders of the governor.

An attempt was made on Fanny-Eleanor’s behalf, a payment of about two thousand dollars, for her to remain living her privileged life in Canada. The money was refused, she learned she must return to Sowangen on the Kennebec River, and she finally made the decision to return. Quiet and reflective, praying as she walked the trails, she considered and reconsidered what her fate there might be as she sat as demurely as one can in a crude Bateaux on her return, under the care of Samuel Harnden to Sowangen.

About age 14–15 when she returned, she chose Abiel Lovejoy as her necessary guardian. Abiel lost his father as a young man and managed to struggle to be successful without the assistance of his father as most of the young men of his era. He spent a great deal of his adult life offering himself as legal guardian to many young girls and boys in the Kennebec River region. Many who knew of his activities believed his motivation stemmed from thinking of himself as their lost parent assisting them in life, unlike leaving them with no direction or assistance, as had been his difficult start as a young adult.

Timothy Noble, several children, and Mary Holmes were taken captive and tramped into Canada. The hired man and two of the boys managed to escape from the chaos and torching of the house and barn that day. The mother Fanny Noble did not remember had died several years before her return to the Kennebec. By that time, her father was indigent, surrounded by filth, living in a deteriorating old cabin on the island. Fanny, now known as Eleanor, could not fathom why she had been returned to such a wretched place to live with an uneducated man she did not remember but who also disgusted her. When she sought out her former local friends, they did not provide much solace. Her broken father had earned his reputation for consuming significant quantities of liquor on a regular basis to ease the pain of losing his family.

Fanny-Eleanor did not understand what her father had gone through. Soon after her return to the island, Fanny’s father passed away, leaving her free to pursue a life independent of the horrors she had endured in her short lifetime. She remembered the kindness she was shown in Canada. She decided to utilize the education she had been privileged to attain, becoming a schoolteacher in New Hampshire, first married to Jonathan Tilton and later to John Shute, at last permanently settling down in that state as Mrs. Shute. Sowangen would be changed forevermore.

Since the first ships sailed up the Kennebec River to explore virgin territory, many lives had been lost or changed, leaving burnt cellar holes as evidence of their rich lives. The Abenaki had been driven north from their homelands to join other refugees of English tactics in Nova Scotia or Quebec, leaving only burial mounds and remnants of seasonal feasts on the Dresden shore. The pristine island vista was left smoldering, smoke wafting for weeks across the river onto either shore of the mighty Kennebec. Both shores had experienced as much change as the three little islands (Spaulding, little Swan, and Sowangen) but the hearts of healthy men and women who had ventured forth from another continent were not easily crushed.

From the first landing on the shores of Sabino, Popham Colony sprang, and some of those residents were bitten with the urge to return to an island they had explored while living at that colony. Resilience is a virtue. Several descendants of the original families would come to build homesteads and farms on the islands. Just as sure as grasses and saplings forged their way through the charred remains of those who first came to love this place, in time enough settlers arrived to populate a small thriving town on the fertile islands, including Kennebec Rivers’ Swan Island, Sowangen – the Island of Eagles.

For more history, photos, how to become a FRIEND OF SWAN ISLAND supporter, and general information about Swan Island click the link:

CINNAMON’S SWAN ISLAND ADVENTURES on the KENNEBEC RIVER in MAINE

FIND CINNAMON’S ADVENTURE BOOKS at:

SHERMANS BOOKSTORES OF MAINE

PEMAQUID SEA GULL RESTAURANT & GIFT SHOP

AMAZON.COM

BARNESANDNOBLE.COM